Welcome to Hebrew Lessons!

On the fascinating and often challenging intersections of language, culture, and American Jewish identity at a particularly fraught moment in history.

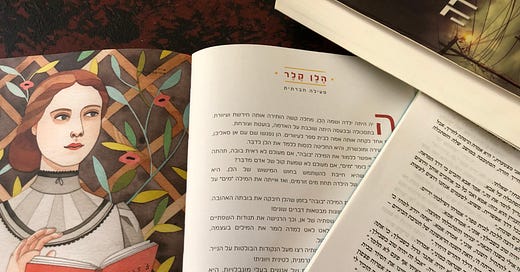

Photo by Harriet Brown

Like many Americans I’m fluent in only one language, English. But like many American Jews, I acquired bits and pieces of another language as I was growing up. Jews of my generation and background—East Coast Conservative Judaism—spent long Saturday mornings in childhood stuffed into formal clothes, squirming in synagogue pews. Sitting through a three-hour-long service, week after week after week, you pick things up.

I got other language lessons as a kid, too. From ages four through 12, I attended a Solomon Schechter Hebrew Day School in Camden, New Jersey (later Cherry Hill). Our teachers were mostly Polish Holocaust survivors who had emigrated to the U.S. after World War II, plus a few sabras who’d left Israel in the postwar period. In the mornings we studied English, history, social studies, math. In the afternoons, our subject was Judaism: history, Bible, ethics—everything in Hebrew.

We were taught about centuries of persecution and heroism, about the Holocaust. We were told that Israel was our ancestral homeland, a place Jews had lived for thousands of years. We were told that we deserved it.

Decades later, as a university professor at a journalism school, I began to teach myself some of the things we didn’t learn back then: About the Nakba, the Arabic term for “the catastrophe,” meaning the establishment of the modern state of Israel in 1948 and the war that followed. About the expulsion of the Palestinians who lived in those villages and towns, the decades of displacement and suffering that followed.

But back then, especially for a nerdy kid like me, it was cool to learn a different language, one with its own alphabet that you wrote from right to left. In New Jersey in the 1960s, Hebrew was a secret code. You could pass messages or doodle notes in it and no one else would understand. Knowing some Hebrew was like having a superpower, and what kid doesn’t want that?

And I was good at the language, quick to grasp the dikduk, the grammar, a strong reader. I loved the way the rolled Rs slid off my tongue, the rasp of the guttural chets. There were no sounds like that in English, so powerful, so sure of themselves.

Language is both an artifact of culture and a lens on it.

Photo by Cole Keister on Unsplash

The Hebrew we learned in the 1960s and 70s in South Jersey was mostly the language of the Bible. It bears about as much resemblance to modern Israeli Hebrew as Biblical English does to Urban Dictionary slang. I was good at Hebrew at school, but I learned just how limited my language skills were when I spent a summer in Israel at age 15, including one memorable weekend when I got stranded over Shabbat with people who spoke no English at all.

As an adult, I rarely went to synagogue and didn’t keep up with the language, though I hung on to some of the things I’d learned . One day when my younger daughter was a rambunctious toddler who wouldn’t come when I called, I opened my mouth and found myself saying !באי הנה עכשיו

Which means come here now! To my shock, she ran right back to me. Maybe it was hearing her mother utter an incomprehensible warning; maybe it was the frustration in my tone. Maybe saying it in Hebrew was like putting on another personality, one that meant business. From then on, whenever I really wanted to get her attention, I used the Hebrew phrase and she flew over like a yoyo snapping back into a waiting hand. It was our secret code now.

That was the extent of my continuing Hebrew until a few years ago, when I started studying the language again. Those adult classes made me realize that contrary to what I’d believed, I sucked at דקדוק

and I had forgotten any vocabulary I’d ever known. I signed up for Ulpan, a weekly group class with other adults from around the world, mostly from Russia, and eventually ponied up for private Ulpan lessons, which I’ve been taking now for about six months.

A lot has happened in the world, especially in the Middle East, since I restarted the study of Hebrew. The West Bank settlements and conflicts, the confinements of Gaza, October 7th, wars in Gaza and Lebanon. And I know I’m not the only American Jew right now who’s trying to process the lessons of the past and the present in new ways, and figure out what I think and how I feel about it all. Many of us are rethinking our complicated history and relationship with Israel—its traditions, its geopolitics, its history, its future.

For me, relearning Hebrew—the language of my childhood and my culture—helps me grapple with these deeply personal and also highly public issues. Language is both an artifact of culture and a lens on it. It is, to paraphrase the poet Adrienne Rich, both the wreck and the story of the wreck, the thing itself and our narratives about the thing.

For me, Hebrew lessons have become much more than the study of grammar, word order, vocabulary. They’re a chance to re-examine everything I thought I knew about being an American Jew, at a time when there aren’t many venues for doing that. It's a space for working through some big questions. I hope you’ll join me.

Oddly, as a classmate of yours, I got a pretty good grounding in דקדוק. That came back to bite me later, though: when I tested for the Ulpan upon moving to Israel, I did so well on that part of the test that they jumped me into the fourth level, despite my having no functional knowledge of contemporary Hebrew. It was like beaming into New York having thinking that I'd have a good grounding in English, despite not knowing of anything after Shakespeare.

Growing up at Beth El, the image that we learned of Israel was that of the happy Chalutzim, all working hard in the fields by day and dancing around the campfires at night. The city that I moved into seven years ago is, of course, much different.